When engineers and manufacturers work with metals, they demand strength and durability. Metal parts are expected to last, and their stress resistance is what makes them useful in applications far and wide.

Sometimes, however, manufacturers need their metals to be soft and ductile. Because when metals are very hard, they are harder to bend, form, and cut into the desired shape. In other words, more ductility and less hardness mean better workability from the metalworker’s perspective.

In metalworking, heat treatment processes like annealing can be used to increase the ductility and reduce hardness of metals to make them more workable. This article looks at how annealing works and how it is used to improve a huge variety of metal (and sometimes non-metal) parts.

What Is the Annealing Process?

Annealing is a heat treatment process that softens metal, reduces its hardness, relieves internal stresses, and increases its ductility. All of these physical changes improve the workability of the metal, making it easier to use in manufacturing processes like bending or machining.

As well as making metals easier to work with, annealing can stabilize a material’s chemical properties and increase the lifespan of the finished metal parts, as it helps prevent fracturing down the line. The process can even be used on non-metal materials like glass and plastics to achieve similar benefits.

How Does Annealing Work?

Annealing works by heating a material above its recrystallization temperature but below its melting point. This allows atoms to move in a process known as diffusion. The heating stage is followed by a period of controlled cooling process, forming new, stress-free grains. Precise control of cooling rates is critical, as overly rapid or slow cooling can negatively affect performance.

The process as a whole realigns the crystal structure of the metal, reducing dislocations and making the metal softer and easier to shape for further manufacturing.

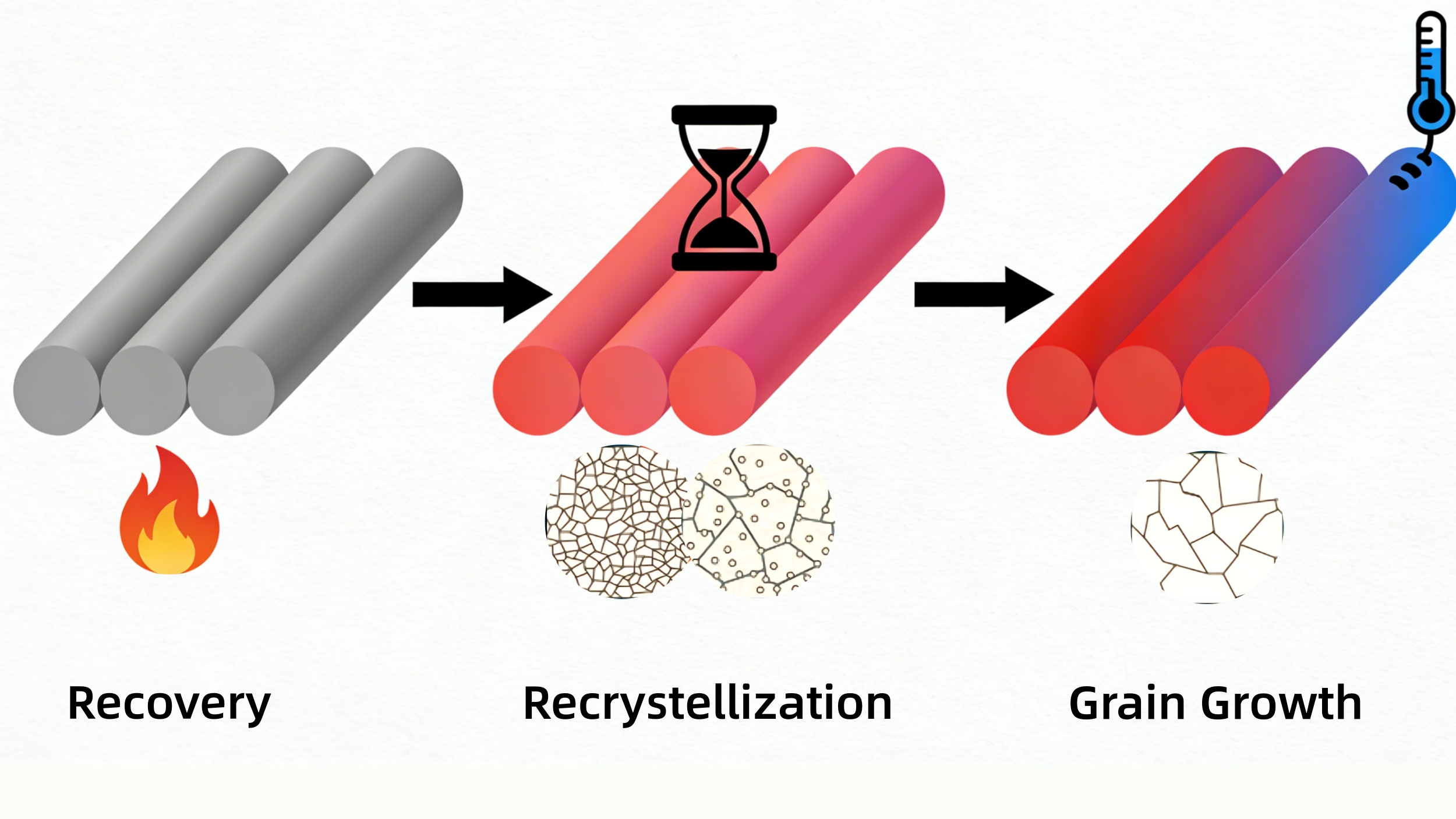

Three Stages of Annealing

1. Recovery

When the temperature of the metal is raised, it goes through a recovery stage—so called because the metal begins to recover its “original,” softer properties.

Recovery softens the metals by removing defects known as dislocations, eliminating internal lattice defects, and reducing residual stresses. This happens because the heat provides energy to the atoms in the crystal lattice, allowing them to move.

2. Recrystallization

The recrystallization stage takes place at the material’s specific recrystallization temperature, higher than before but below the melting point. During this stage, new strain-free grains nucleate and replace their deformed predecessors.

3. Grain Growth

Grain growth, the third stage, only occurs if the annealing process continues beyond full recrystallization.

During the grain growth stage, the size of individual grains increases. This causes the microstructure of the material to coarsen, which can further improve softness and ductility but can ultimately weaken the material.

Types of Annealing

Different annealing types or variants can result in different effects. These annealing subtypes include:

- Stress Relief Annealing: Involves low-temperature heating of the material to relieve internal stresses from welding, casting, or machining, followed by slow cooling.

- Process Annealing: Also called intermediate annealing, subcritical annealing, or in-process annealing. Restores ductility in between cold working stages without fully softening the material.

- Full Annealing: Used to significantly improve ductility, particularly of steel. Involves heating the material above critical temperature, holding it, then cooling very slowly to create uniform ferrite-pearlite structure.

- Isothermal Annealing: Involves heating the materialto form austenite, followed by rapid cooling and holding to complete the pearlitic transformation and create uniform hardness.

- Diffusion Annealing: Also called homogenizing, involves high temperatures to reduce segregation.

- Solution Annealing: Involves heating the alloy—typically austenitic stainless steel—to high temperatures to dissolve precipitates into solid solution, then rapidly cooling to retain corrosion resistan

- Bright Annealing: Involves use of an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation and produce a “bright” surface finish.

- Short Cycle Annealing: Involves repeat cycles of heating and cooling to turn normal ferrite into malleable ferrite.

- Spheroidizing: Involves heating the material just below the critical temperature for a long time. Make high-carbon steels easily machinable by forming spherical carbide structures (spheroids).

| Heat Treatment | Purpose | Temperature

Change |

Effect on Hardness | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing | Soften material, relieve stresses, improve workability | Heated to high temperature then slow cooled | ↓ | Forming, machining prep |

| Normalizing | Refine grain structure, improve uniformity | Heated to very high temperature then air cooled | ↓ | Structural steels |

| Quenching | Maximize hardness and strength | Heated to very high temperature then rapidly cooled | ↑↑ | Cutting tools, wear-resistant parts |

| Tempering | Reduce brittleness after quenching | Heated to moderate temperature then cooled | ↓ | Hardened steel parts needing toughness |

How Annealing Improves Material Workability and Machinability

Annealing is an essential process for preparing metals for other manufacturing processes. It does this by increasing ductility, allowing metals and other materials to undergo plastic deformation without breaking.

Annealing improves material workability and machinability in the following ways:

- Increases ductility: Atomic diffusion reduces the number of dislocations (defects) in the crystal structure, restoring ductility and preventing the likelihood of fracturing.

- Reduces brittleness: Greater ductility means less brittleness, which means the metal can be freely bent, pressed, or shaped without cracking.

- Increases softness: The softer metal is easier for the machine tool to cut through, allowing for faster and more precise cuts.

- Reduces tool wear: The softer and less abrasive material is more friendly to the cutting tool, prolonging tool life.

These advantages make annealing especially valuable when working with ferrous metals such as steel and cast iron.

Annealing pros and cons are different to those of other heat treatment processes. All of the above can be considered key benefits of annealing; however, anneal disadvantages include high energy use, time required, and risk of over-annealing and excessive grain growth that can cause weakness in the material.

How Annealed Materials Are Used in Manufacturing Processes

Metals that have undergone annealing can be easier to manufacture using a range of forming and cutting processes. Below we look at how annealing can help these different techniques.

CNC Machining

Annealing can be used before and after CNC machining to improve the quality of machined parts.

Prior to machining, annealing can be used to soften metals, making them easier to cut with precision and reducing potential tool wear. After machining, annealing can be deployed to remove stresses caused by the cutting process.

Forming and Bending

Annealing makes metals easier to bend without breaking, making it ideal for forming and bending processes in which the metals are significantly deformed. Annealing reverses the work hardening caused by prior operations, preparing it for further work.

Stamping and Deep Drawing

The process of annealing is ideal for cold working processes like stamping and deep drawing, as it decreases the brittleness of the material and helps prevent failure.

Welding

Annealing makes metals softer and more pliable, which allows for welding without the risk of the material fracturing.

For materials like some stainless steels and nickel alloys, pre-weld heat treatment such as annealing is useful for decreasing crack sensitivity and ensuring a strong, reliable weld joint. Furthermore, annealing after welding is used to relieve internal stresses, soften the brittle heat-affected zone (HAZ) following intense heat, and restore the metal’s ductility and toughness.

3D Printing

The processes described above involve the annealing of metals such as steel, aluminum, and titanium. However, it can also be used to prolong the lifespan of thermoplastic 3D printed parts.

In 3D print annealing, the plastic parts are heated to just below their glass transition temperature, causing disorganized polymer chains to align into a more crystalline structure. This makes the part stronger, harder, and more heat-resistant.

Applications of Annealing

Annealing is used across many industries to reduce hardness, improve ductility, and relieve internal stresses, ultimately making parts more durable. Common annealed parts include:

- General manufacturing: Cold rolled sheet metal, drawn aluminum, wire, and welded assemblies

- Construction: Hydraulic cylinders, crankshafts, pistons

- Automotive: Axle shafts, gears, engine parts

- Aerospace: Frames, landing gear, engine parts, titanium alloy parts

- Electronics: Semiconductor wafers, copper, and aluminum conductors

Metals and Alloys for Annealing

Several metals and alloys are suitable for annealing, though different temperatures (and annealing types) suit different materials. The table below shows suitable temperatures for different metals, in addition to the extra benefits it provides on top of improved ductility.

| Metal | Typical Annealing Temperature | Unique Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Low-carbon steel | 750–900 °C | |

| Medium-carbon steel | 800–850 °C | |

| Alloy steel | 750–900 °C | |

| Stainless steel (austenitic) | 1,000–1,100 °C | Restores corrosion resistance by dissolving chromium carbides |

| Stainless steel (ferritic) | 750–850 °C | |

| Cast iron | 800–950 °C | Converts combined carbon to free graphite to improve damping |

| Aluminum | 300–415 °C | Restores electrical conductivity after cold work |

| Copper | 400–650 °C | Maximizes electrical and thermal conductivity |

| Brass | 450–650 °C | Prevents stress-corrosion cracking during cold working |

| Bronze | 500–700 °C | Improves wear compatibility in bearing alloys |

| Titanium | 650–760 °C | Prevents hydrogen embrittlement |

| Nickel and nickel alloys | 700–1,100 °C | Restores oxidation resistance at high temperatures |

Conclusion

Annealing provides important benefits during metalworking, allowing manufacturers to carry out processes like forming and machining without damaging the metal stock. Its many subtypes mean it is a versatile process suited to various alloys and applications.

Emerging industrial uses of annealing include its use in additive manufacturing, where weaknesses inherent to 3D printing—internal stresses and voids—can be mitigated through heat treatment. Another contemporary application of annealing is in semiconductor manufacturing, where advanced processes like laser annealing and microwave annealing can target specific functional layers in 3D chips.

Whatever your annealing needs, the metalworking specialists at 3ERP can use our years of experience to realize your project. Request a quote here.

FAQs

What are the three stages of annealing?

The three stages of annealing are recovery (creates movement of atoms), recrystallization (enables nucleation of strain-free grains), and grain growth (further altering mechanical properties).

What is magnetic annealing?

Magnetic annealing is a specialized heat treatment for soft magnetic materials that requires a controlled atmosphere. The process provides the regular benefits of annealing while also improving magnetic properties.

What is an annealing furnace?

An annealing furnace is an industrial oven that can precisely generate and maintain the high temperatures required during annealing. Cooling of the metals also typically occurs within the furnace.

Is annealing stainless steel possible?

Yes, annealing of stainless steel is common, though it requires high temperatures. Solution annealing is often used for austenitic grades.

Is annealing gold possible?

Gold annealing is a fairly common process in jewelry making and other industries. Because the workpieces are typically very small, jewelers often use a special torch rather than a furnace, heating the gold until it glows red.